ALL SECTIONS

Africa’s missed opportunity?

Six years after its signing, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) remains more promise than progress – hindered by weak implementation, structural barriers, and deep-rooted political and economic challenges

Featured | Investment Management | Wealth Management

Author: John Muchira, Features Writer

Top 5

- Top 5 female-fronted fintech firms

- Top 5 Latin American tech hubs

- Top 5 sustainability pioneers in Europe

- Top 5 keys to global economic recovery

- Top 5 WFH habits, according to the world’s most successful business leaders

- Top 5 pandemic-proof industries

- Top 5 countries to be world’s next manufacturing hubs

- Top 5 most influential and inspirational US economists

- Top 5 ways to boost employee engagement and commitment

- Top 5 financial services that are ripe for automation

- Top 5 ways that GDPR has impacted digital banking

- Top 5 emerging fintech hubs across the globe right now

- Top 5 ways that the finance industry can prepare for AI

- Top 5 economic risk factors that must be considered

- Top 5 tips for retailers looking to sell into Chinese market

Historically, Africa has been consistent in creating a pattern of pursuing integration through grand masterplans. Many have remained just plans on paper due to mediocre implementation. A similar trend is shaping up with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), an agreement that was touted as the holy grail in revolutionising trade, investments and economic development.

On May 30, the continent marked the sixth anniversary of the signing of the AfCFTA agreement. Like many other grandeur treaties, AfCFTA is at the risk of losing its allure. Granted, only Eritrea has openly called the agreement pointless and opted to keep away. Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali have been suspended after military juntas instigated coups. In essence, 45 countries of a total of 48 that have ratified the agreement believe in the principles of AfCFTA. In reality, this is as far it goes – belief in the ideals of the agreement.

Africa Kiiza, PhD Fellow at Germany’s Universität Hamburg, captures the picture. “The aspirations and ambitions of AfCFTA are brilliant. The problem was in putting the cart before the horse,” he says. He explains that, in desperation, African leaders rushed in signing a ‘shell’ of an agreement hoping to resolve a mountain of obstacles along the way. Evidently, tackling the hurdles amid shifting internal and external geopolitical and economic landscapes is proving herculean.

On aspirations, the continent did paint a rosy picture. First was the elevation of AfCFTA to the pinnacle of Agenda 2063, putting the agreement as one of the flagship projects. The expectation was that the agreement would be the ultimate solution in resolving fundamental economic problems bedeviling the continent, namely low levels of integration, overreliance on commodity exports and limited market access for African businesses. By creating a single market for goods and services, the agreement would solidly lay the foundations for the establishment of a continental customs union. Notably, these are key preconditions for the establishment of the African Economic Community.

Boosting intra-Africa trade

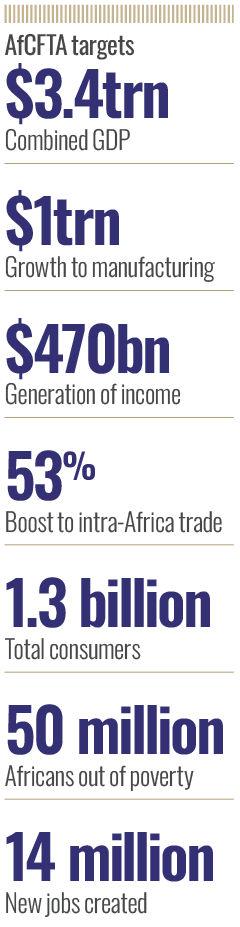

For AfCFTA, the goals are clear-cut, at least on paper. The overriding goal is the creation of a single market of 1.3 billion consumers with a combined gross domestic product of $3.4trn. It has other vast benefits. Most prominent is boosting intra-Africa trade by 53 percent, growing the manufacturing sector by $1trn, generating income worth $470bn, creating 14 million jobs and lifting 50 million Africans – or 1.5 percent of the continent’s population – out of poverty.

The fact is that Africa’s future is being imagined through frameworks imported from elsewhere

Six years down the line, the realities of putting the cart before the horse are glaring, with some bordering on absurdity. A case in point is the fact the AfCFTA Secretariat, which was established in 2020, continues to be financed by the German development agency GIZ, which also finances negotiations besides offering technical assistance. Thanks to GIZ, progress has been achieved on the legal construct of the agreement cutting across rules of origin for some sectors, dispute settlement mechanism and digital trade, among others.

GIZ’s support cannot be underestimated. However, it has exposed Africa on two fronts, one being administrative inefficiency and the other being the tendency to cling to the dependence of the ‘economy of borrowed institutions.’ “The fact is that Africa’s future is being imagined through frameworks imported from elsewhere,” observes Prof Dunia Zongwe, Associate Professor of Law at the University of Namibia. He adds that the situation is complicated by deep-running historical ideological tensions between Africa’s neoliberal and Pan-Africanist doctrines that have catalysed the continent’s integration curse for decades.

Slower than expected trading levels

The impact has been a slow implementation of AfCFTA. Prior to the signing of the agreement, total formal trade within the continent totaled between 12 and 18 percent. In 2022, the Guided Trade Initiative was launched to kick start actual trading under AfCFTA. Yet, intra-Africa trade remains at below 20 percent. Last year, trade between African countries rose by 7.7 percent to hit $208bn, according to the African Export-Import Bank. The level of value addition remains lacklustre, with total value of exports standing at $682bn and imports $719bn.

By the end of 2024, 31 countries out of the 45 had initiated some form of trade, albeit quite negligible. The growing number, a significant increase from seven in 2023, coupled by the adoption of three new protocols on investments, intellectual property and competition, are a demonstration that Africa is committed to building momentum in deepening the goals of the framework. The ultimate hope is to increase intra-African trade to 53 percent, putting it on par with other continents where intra-trade is booming. In Europe, it stands at 68 percent, Asia at 59 percent and North America at 51 percent.

“The fruits of the trading bloc are low-hanging, but they will ripen incrementally depending on the implementation of the agreement,” observes Prof Zongwe. He adds that, so far, the continent is performing dismally, with a low policy implementation rate of only seven percent. Even the Africa Union (AU), the highest governing body, has admitted that so far, it has been a case of misses rather than hits on AfCFTA.

A number of obstacles to overcome

The reality is emerging that to make AfCFTA work and for Africa to realise the full benefits, the difficult task lies in tackling the myriad structural, logistical, political, economic and other obstacles facing the agreement.

Addressing these challenges is proving to be slippery mainly because most countries, particularly the least developed, peg their development on inward looking as opposed to outward integration. Most aver that AfCFTA is ultimately designed to benefit the big economies that are in desperate need of new markets for their goods and services. For them (small economies), the agreement is a pursuit of profits as opposed to equality.

Kiiza gives practical examples. A US citizen has the luxury of traveling to 24 African countries without a visa. For a Uganda national, the same applies to only nine countries. This sorry state of affairs has come about by the deliberate refusal by countries to ratify the AU’s protocol on free movement of persons. Only four countries have ratified the protocol.

It gets worse. Despite being a major producer of cocoa, only second to Côte d’Ivoire and accounting for a quarter of global production, chocolate exports from Ghana to South Africa attract 30 percent in tariffs. For Switzerland, chocolate exports to South Africa attract zero tariffs.

If that is not preposterous enough for a continent craving integration, the economic disparity gives context. Burundi, whose economy is worth $3bn, is expected to open 97 percent of its market. The same applies to Nigeria, with a $487bn economy.

“The idea that liberalisation and tariff removal before building the capacity of small nations will automatically increase trade is flawed,” notes Kiiza. He adds that the continent must apply brakes on political expediency and focus on the fundamental blocks that will make AfCFTA work.

In fact, the inability of the various regional economic community blocs to flourish, despite being the foundations on which AfCFTA stands, offers vital lessons. The East Africa Community (EAC), for instance, is disintegrating due to political and economic rivalry.

Expensive barriers in the way

Top on the list of enablers that need fixing is the infrastructure conundrum. Undoubtedly, poor transportation networks, inadequate logistics systems, and inefficient border procedures are huge obstacles to trade. The physical barriers make it more expensive for businesses in Africa to trade with each other than with partners outside the continent. It is not hard to see why. In sea trade, for instance, 98 percent of shipping lines are foreign owned. For them, it makes economic sense to flood Africa with foreign-made goods that struggle to fill a container with goods produced in the continent. The challenge extends to rail transportation, where low investments have bred insignificant connectivity at a mere 0.1 percent.

While poor connectivity is a major factor in the high costs of goods produced in Africa, non-tariff barriers (NTBs) have become the toys of trade in pursuing political interests and entrenching protectionism. Subsidies, import bans, complex customs procedures, regulatory inconsistencies, corruption and other administrative hurdles continue to impede cross-border trade. In EAC, for instance, the direct cost of NTBs was estimated at $17m in 2023. Considering that AfCFTA lacks any prohibition on subsidies, which together with dumping cases count among the most litigated issues before the World Trade Organisation, it means Africa can expect NTBs to continue being used to undermine fair competition.

On tariffs, the continent has structured a progressive reduction over a 15-year period, with the ultimate goal being to liberalise 97 percent of goods by 2034. This is already proving problematic, with many of the scheduled tariff reductions yet to take effect, yet the deadline is less than a decade away. “Some countries balk at fully opening their markets because they fear losing revenue from tariff reductions or the adverse effects of stiffer competition on domestic industries,” says Prof Zongwe. He adds the fear emanates from the fact that, for most countries, the production structures are largely similar.

As a pain-reducing mitigation on the effects of tariff reduction, the continent has a $10bn Trade Adjustment Fund in place. Apart from mitigating potential negative impacts, such as tariff revenue losses and market disruptions, the fund will also be utilised in addressing the infrastructure deficits and supply chain bottlenecks. This is critical because Africa understands that for AfCFTA to have any semblance of success, the continent must break from the colonial yoke of exporting raw materials and commodities and importing finished goods. Essentially, value addition must become the new mantra.

Post navigation

Previous article

India rising: the world’s newest growth giant

Related:

- India rising: the world’s newest growth giant

- Exploring AI’s influence on market dynamics

- How leadership can create a culture of success

- Indonesia’s long-serving finance minister is still standing firm

- Putin’s Arctic ambitions

- 15 years later

- What is eating Europe’s food system?

- Gaming the market

- Europe can’t rearm its way to security

- Jensen Huang: All in on AI